Three questions answered in this article:

– What challenges do Nigeria face in matching population growth with agricultural production?

– How can clear objectives guide proposed solutions to ensure food security and agricultural stability in Nigeria?

– What role does strong legislation play in boosting efforts to improve food security and agricultural exports in Nigeria?

Nigeria’s domestic agricultural and food requirements must match our world-topping population growth. It is a no-brainer! We need more focus on this increasing gap between the capacity to produce food and supply it at affordable prices and our booming populace.

The country’s population grows at an eye-popping rate of between 2.1% and 2.4% per year. To put this in an understandable context, if we start with a base of 234 million in January 2025, 17 million people would have been added to the population by the end of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s first presidential term in 2027. This figure is about 50% of Ghana’s current population —a country we closely compare ourselves with. By 2031, at the end of President Tinubu’s possible two-term presidency, we would have added about 50 million people, more than the combined populations of Ghana and the Republic of Benin.

In essence, we should be planning and executing our agriculture like we are growing at the rate of two countries put together.

A case for tertiary institutions driving agricultural transformation

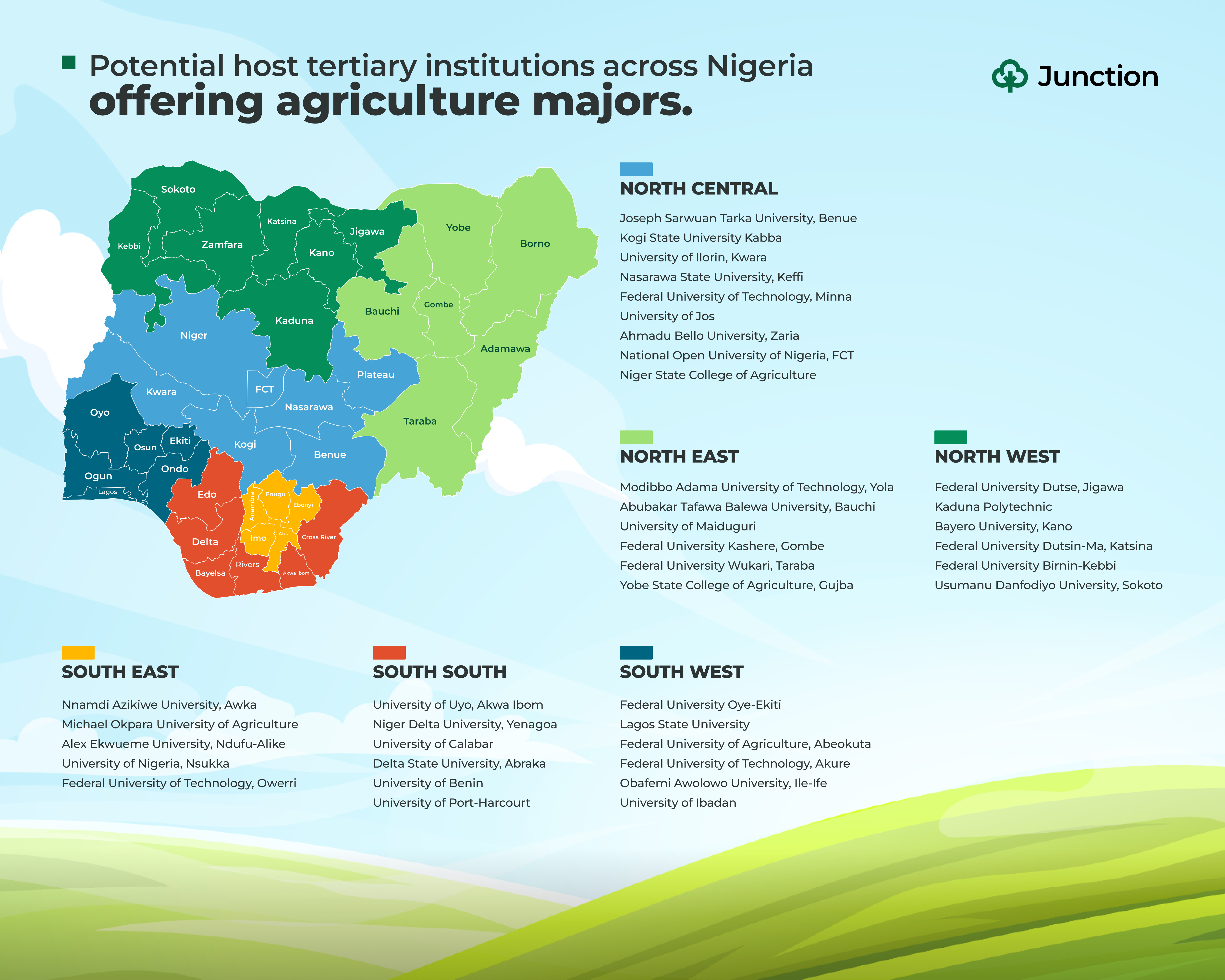

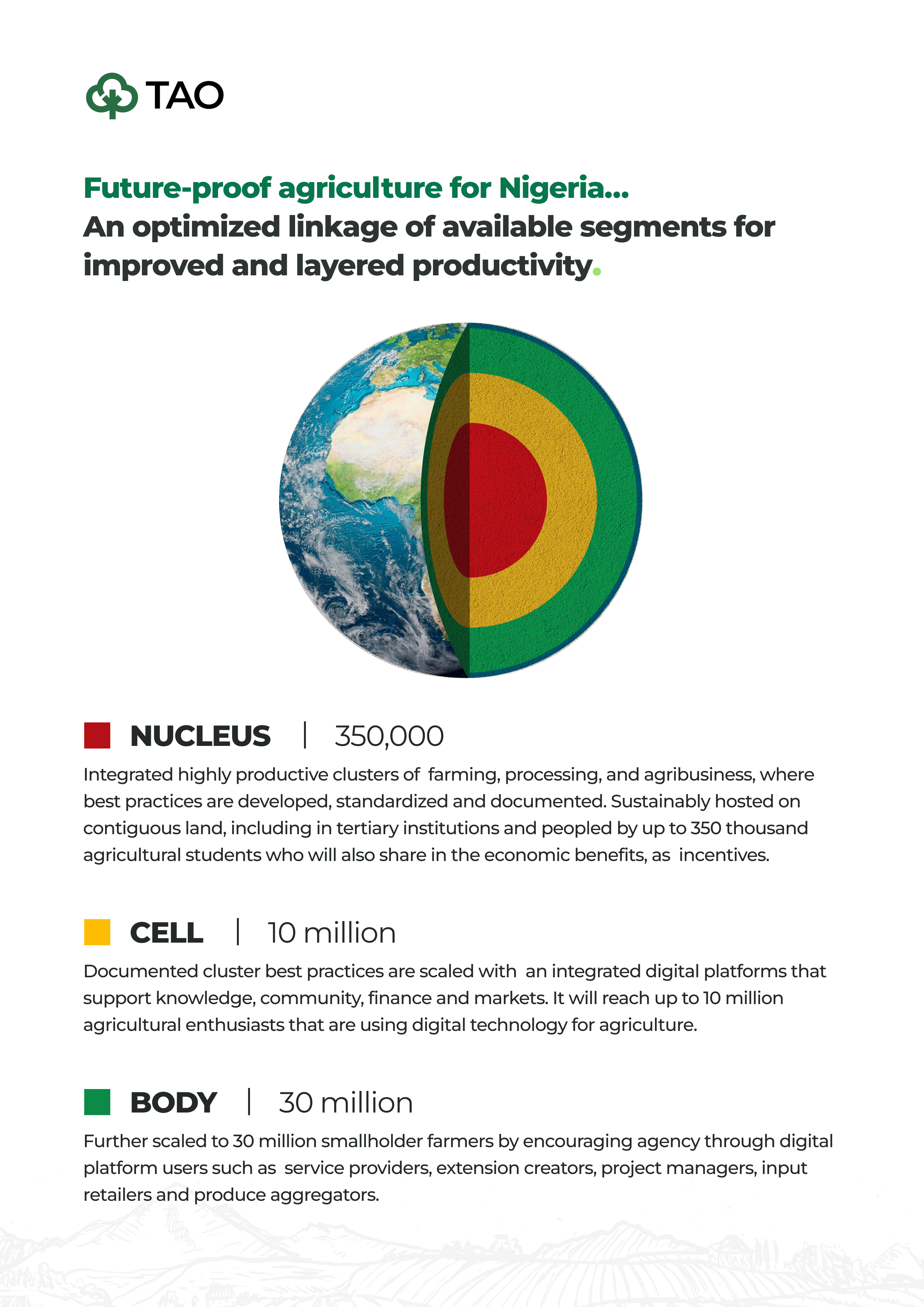

By my count and estimation, Nigeria has about 144 tertiary institutions, holding an average of 10,000 hectares of land each, and teaching about 350,000 young people agriculture. This is a potentially potent asset in the outlook for food security.

Consider that the population of farmers in the Netherlands is about 45,000 and they exported agriculture products worth €123.8 billion in 2023, more than a third of Nigeria’s entire gross domestic product (GDP).

Although the idea of deploying tertiary institutions for agricultural production to support food security is not novel, clear approaches and intended outcomes with measurable quantitative and qualitative objectives are usually missing in such discourse. I will take the conversation forward by proposing these missing elements.

A need for clear objectives

Using tertiary institutions to support Nigeria’s agricultural and food industry may seem laudable on the surface, even noble. However, without clear unit and national objectives, it may quickly turn into a white elephant project with little long-term benefit. This has been the case for many past agricultural and developmental initiatives.

A programme like this must set out with clear tactical and strategic objectives, protocols and coordination for net national benefit for the immediate and long term.

For it to be done right, a partnership with agriculture-focused tertiary institutions, and those that offer agricultural majors, must establish a commercial agricultural system that will be guided by a clear mandate such as:

- Produce 20% of Nigeria’s food requirement at any point in time, with an annual growth rate that is double the annual population growth rate (2.4%), up to the point of possessing the ability to ensure food availability and price stability on short notice when required.

- Produce 10% of Nigeria’s agricultural export requirement as determined by the agricultural contribution to the national budget and forex benchmarks and grow at a rate that is reflective of the national effort in diversifying from a petroleum-based foreign exchange receipt.

- Produce 12,000 well-rounded highly educated and skilled commercial farmers that will produce and process on an average of 50 hectares each, with superior yield, that adds 600,000 highly productive hectares to Nigeria’s agricultural production base annually.

These mandates must integrate with Nigeria’s food security architecture in specific ways, like supplying into the strategic food reserves and supporting the growth of the agricultural industry through the supply of well-educated and skilled practitioners.

A system that compliments staple food security and farmer development

Each unit of the proposed system must farm, process, store and market complementary components of Nigeria’s stable food bouquet. Food items such as rice, maize, beans, dairy, beef and fish must have high priority. These units will be fully integrated into a system consisting of 37 agriculture-focused tertiary institutions spread around Nigeria’s 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory.

Each unit will operate commercially and will be allocated the bouquet component that it is best positioned to deliver effectively and efficiently, using competitive advantages in factors of production and environment.

An important mandate of the units will be to provide participating students with hands-on experience and training in modern agricultural practices with financial benefits, and rotations to other units in the system. The aim here is to improve their roundness, and prepare them to become high-quality, bankable commercial farmers who can support the expansion of Nigeria’s agricultural industry.

Clear components that support mandate delivery

To support the delivery of clear mandates, participating institutions will set up commercially viable integrated agricultural enterprises that imbibe the principles of a circular economy and are staffed by students in training. This will culminate in a system of connected agricultural communities with each unit possessing the following components:

- A competitive and prestigious 3-year programme of 1,000 agriculture students of each host tertiary institution at any time. These students will operate commercially viable contract agriculture for the unit as part of their education and appreciation of a career in agriculture after school.

- Year-round cultivation of allocated crops on contiguous land, using irrigation, mechanisation, and precision agriculture for superior yield performance, or year-round livestock production as indicative of the component of the bouquet allocated to each unit.

- Low complexity input manufacturing and produce processing facilities, operated by participating students on host tertiary institution campuses, to deliver robust training and commercial appreciation, cost efficiency and reduction in post-harvest losses.

- Digitalise the best practices and interactions of the system and distribute them with a platform that will reach other farmers outside of the programme.

Public and private ownership for strategic and tactical deployment

This system should operate in a public, private and people partnership. The people component represents students who will be integral partners with economic benefits. The public through the federal and state governments should own not more than 40% of the individual entities and total system, while private entities will own 60%. Capable commercial agricultural operators and system integrators must be invited to own and manage land, mechanisation, processing, technology and utility components. Commercial operators must provide performance guarantees to demonstrate capacity and full alignment of interests.

During normal economic periods, the system will interact with the market in typical commercial models, selling its output directly into consumers markets, according to its strategic outlooks and plans, and as dictated by market forces. However, during extraordinary periods, occasioned by situations such as high food prices and low availability, through its 40% ownership, the public sector should deploy some or all of the system output of up to 20% of national food requirements towards availability and price stability objectives.

Additionally, the system must be designed to support a strategic agricultural export outlook for foreign exchange receipts, as required.

Built around people with strong mechanisms for student and faculty participation

Beyond food security and price stability objectives, the system should supply educated and well-rounded farmers and agriculturalists to support the development of Nigeria’s agricultural industry. Hence, a need to intentionally build a people component into it.

To deliver this goal, the programme will be positioned as a prestigious student internship, with stringent eligibility criteria that include good academic standing at Cumulative Grade Point Average (CGPA) of 3.5 points or higher and school attendance of above 90%. These criteria are indicators of strong character, diligence, responsibility, and self-leadership which are necessary for success in the combination of academics and rigorous vocational and operational responsibilities.

Tracking quantitative results and ensuring realisable benefits

As a foundational deployment for Nigeria’s agricultural transformation, the system must produce strong quantitative and qualitative results. These results should translate into a better food security situation and an agricultural export-led economy.

To achieve this, each student participant, unit and the total system must have clear quantitative performance metrics that deliver benefits to stakeholders. The student participants, who need to be incentivised to perform optimally and take agriculture as a viable economic option, should contribute to a pool of highly productive farmers and agriculturist base for Nigeria.

Strong laws and structure to support

Any system that supports and guarantees food security and agricultural industry development should be backed by strong legislation and coordinating structures that ensure it attains its full potential on time, within budget, and for the desired outcomes to be achieved on a long-term basis.

Strong laws must safeguard private sector investments, protecting their interests. A coordinated administration structure ensures the system is managed effectively, with clear lines of authority and responsibility to support its complementarity and systemic outlook. It will also facilitate inter-agency and institutional collaboration among different government agencies and tertiary institutions that will support the system, thereby minimising duplication of efforts and ensuring a cohesive approach.

A well-defined administration structure enhances accountability, ensuring that officials are held responsible for their actions and decisions, promoting a conducive environment for private sector participation, and attracting investments and expertise.

Conclusion

There is no time as important as this to create a lasting impact and legacy in improving Nigeria’s agricultural productivity. Agricultural solutions to the three-pronged and interdependent challenges of food insecurity, foreign exchange earnings and youth unemployment require bold ideas and innovation. The opportunity that a mix of educated young people, finance, technology, irrigable land, and mechanisation will provide for exponential leaps in agriculture will leave a legacy that will last for decades.

A noble attempt but execution has always held us back in this nation.

I agree with you this is laudable. Hmmm, it would take a lot of efforts for this to come to play but this is doable.