Questions answered here: - How can agriculture transformation through better financing be achieved in Nigeria by taking a leaf from how Dangote's refinery was financed? - What value can be derived from a well-financed agriculture layered on well-cultivated land? - What will be the benefits of a public, private, and people partnership to deliver agricultural ventures that deliver land clearing, irrigation, and mechanisation?

Transportation and food constitute two of Nigeria’s most pressing sustainability requirements as they contribute the most weight to the population’s non-discretionary spending. These items drain foreign exchange availability and earning potential. Addressing them is crucial for placing the country on a sustainable economic path.

In agriculture, science and best practice suggest irrigation contributes to optimal yield in and out of the rainy season. Unfortunately, reliance on annual single-cycle rain-fed farming hinders Nigeria’s agricultural productivity. It makes it so that cultivated land reaches less than its production capacity, for example rice production is 50% less than the country’s land potential. Inadequate, poorly managed and inaccessible irrigation systems contribute to this hindrance.

To put this in context, Nigeria only irrigates about 207 thousand hectares, which is about 0.9% of its cultivated land and 0.3% of its total agricultural land, as of 2017. This results in the average annual productivity of cereal crops, such as rice, per hectare of land, being as low as 1.2 tons compared to Vietnam’s, which stands at 16.5 tons per hectare annually. Note that Vietnam has similar socio-economic indices as Nigeria, with 20% of Nigeria’s cultivated land, but irrigates over 66% of its cultivated land.

Table 1:

Because of reliance on rain-fed farming, most smallholder farmers, who contribute to about 98% of Nigeria’s food production, can only produce in a single farming cycle out of a possible three to four farming cycles per year. This represents a paltry one-quarter capacity utilisation of their most important agricultural asset, land. Furthermore, the country’s situation diminishes smallholder farmers’ earning potential because agricultural production growth is a factor of either yield per hectare or land capacity usage. It also hinders Nigeria from reaching its total agricultural productivity potential.

This inefficiency has a ripple effect throughout the entire agricultural value chain, impacting mechanisation, transportation, processing, storage, and ultimately, the market and earnings. For example, they limit staple cereal production to only one farming cycle out of a possible three, or 3-4 months of production per year of 12 months. The rest of the year without production experiences swinging availability and pricing, which allows for speculation and reduces capacity utilisation in downstream industries like processing and milling. Ultimately, the country resorts to food importation which distorts economic indices such as food prices and increases pressure on the naira.

Transforming the agricultural sector in Nigeria requires new thinking, bold ideas, creative financing, improved farmer and agriculturist profile to focus on young people and technology. Most importantly, the private sector must participate to achieve financing and delivery efficiency, effectiveness, and an explosion of innovation.

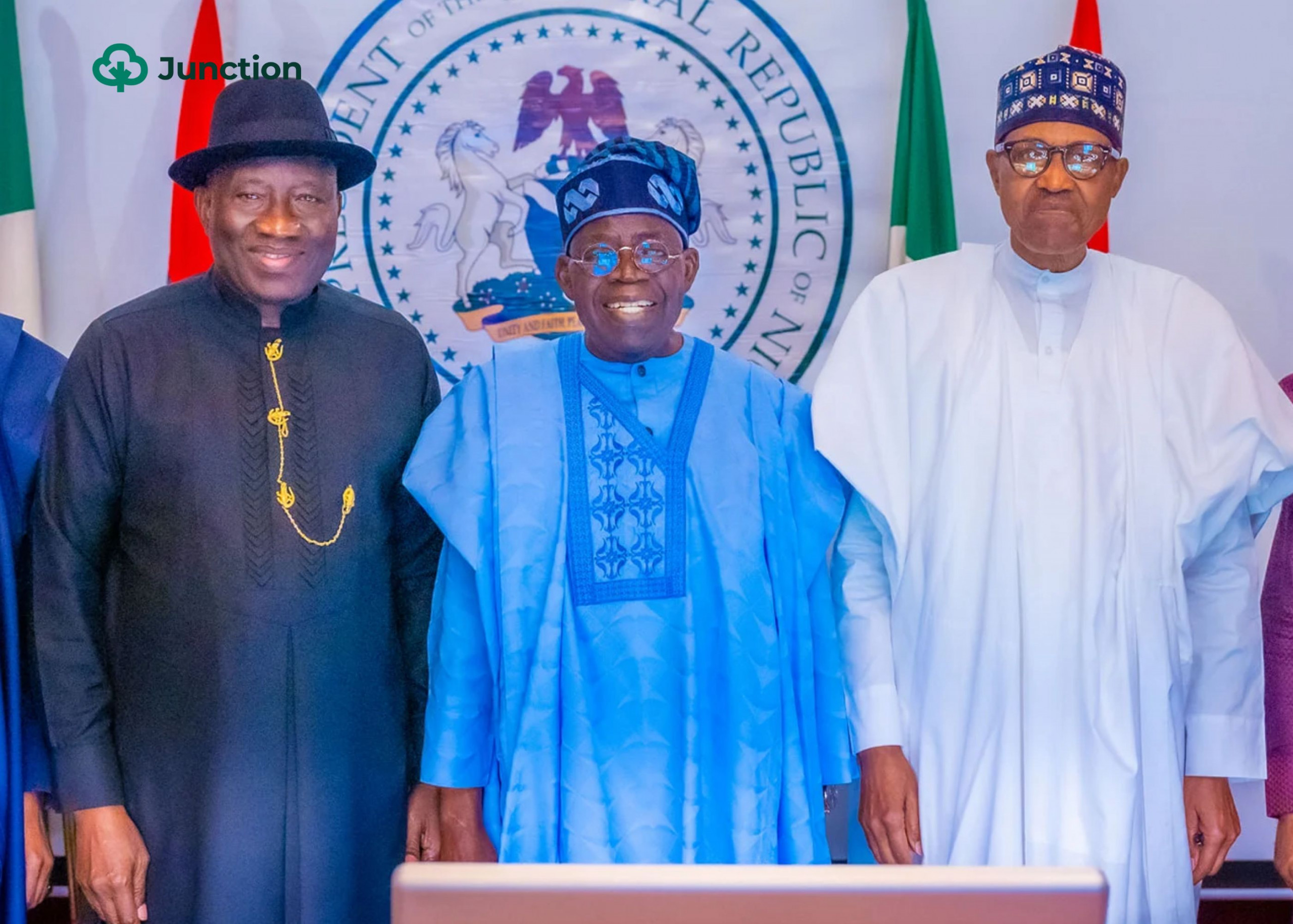

This article focuses on garnering finance for agriculture by taking a leaf from how Dangote financed his petroleum refinery in Lagos state. It bases its approach to financing on President Tinubu’s promise for the sector. It also suggests a financing model that takes all contributing parties into account.

Attaining high productivity requires a new approach

Nigeria’s agricultural production will improve exponentially with concerted efforts towards delivering well-structured and managed medium to long-term capability and capacity for land clearing and irrigation. Adding logistics and processing capacity for integrated year-round farming and processing will further drive this needed change. Interestingly, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s Renewed Hope manifesto focuses on these elements in its agricultural and youth employment outlooks.

Increasing land utilisation and improving processing will increase unrestricted farming and agricultural production cycles. The current reality is such that farmers must align their cropping calendar to rain cycles at high precision. Unfortunately, and often, they can’t be precise because other factors of production, such as input or funds, are unavailable at the right time to align perfectly. Usually, many farmers miss timing their cultivation to the rain cycles for the best results. Some miss the rain cycle completely, leaving them unproductive for up to one year in some instances and rendering their entire value chain unproductive. With properly irrigated and cleared land, farming can start anytime, and farmers can begin production when they are ready and able without waiting for any particular factor they have no control over.

Transforming primary agricultural production for local consumption and export

A national agenda for agricultural transformation intersecting with youth engagement will bring significant benefits in terms of agriculture and employment. However, optimal financing and execution determine these benefits. One effective approach is implementing integrated land clearing, irrigation, mechanisation, processing, and logistics on contiguous clustered land, that are production hubs. Employing service models and involving the private sector can lead to optimal agricultural production. In turn, it will generate favourable returns on investment greatly enhancing productivity, output and food security.

A cursory analysis of Tinubu’s outlook indicates that it can add about 143 million tons of grains (assuming all effort is focused on grain production) to the country’s agricultural output. This production has a US$79 billion farm gate value and up to four times that of total GDP impact. Also, note that US$79 billion in farmgate value is already 76% of agriculture’s contribution to Nigeria’s GDP in 2022.

In execution, there is need to consider delivering capabilities that include farm integration, market capacity, and creating quantitative measures of success, such as 1 million farmers holding an average of about 28 hectares of farmland. These farms could integrate processing and employ about 10 people each. They could, in turn, catalyse and support 5,000 businesses in areas such as mechanisation, transportation, and storage, at an average venture value of about US$ 10 million.

Table 2:

The areas of agricultural component that the private sector will support by way of financing and technical capacity must aim to produce food and raw materials for local demand and supply to the export market. A 70/30 local market and export mix can be the targeted for a start. This outlook will contribute towards reducing pressure on the Naira from food and raw material importation and improving foreign exchange earnings.

Table 3:

Adapting Dangote Refinery’s approach to finance

In Nigeria, food, and by extension agriculture, is chugging along, albeit inefficiently, with looming dangers of future inadequacies as the population grows. With little practical government support, it carries on in fragments and through farmers’ share will. Agriculture and food production is leaving a lot on the table as it fails in their potential to feed the nation, guarantee food security, create millions of jobs, and create export opportunities for foreign exchange earnings.

Nigeria’s refined petroleum product requirement demanded a similarly serious pivotal effort as its local production was in worse shape than agriculture. From the private sector angle, Dangote took the charge, galvanising financing across government, local and international financial services. The result is a 650,000 barrels per day (BPD) integrated refinery project.

Agriculture in the country needs the same kind of move. Even if not by a single entity, at least by a tight-knit and focused group of private sector participants, rousing public and private sector support at local and international levels.

It is essential to take a cue from and implement a Dangote-like effort in agriculture as it promises to deliver benefits in multiples of what the refinery could deliver. As exemplary and noteworthy as it is, the Dangote refinery will create only about 135 thousand permanent jobs. Meanwhile, the same finance will create up to 10 million direct jobs in agriculture and other outsized benefits, as already declared. Also, it can potentially deepen the diversity of wealth and value, which then mobilises more actors across a broader section of the economy.

The economics of a closely knit private sector-led consortium approach to delivering Nigeria’s agriculture transformation agenda, that will integrate youth employment are sound. However, it requires an ambitious outlook and big thinking, including significant cost and financial considerations. Therefore, applying new thinking and bold ideas to financing and managing this effort is imperative.

From a cost and delivery perspective, it could cost about US$41 billion in capital expenditure and US$34 billion in operating expenses to increase Nigeria’s arable land under cultivation from 35% to 65% as President Tinubu’s manifesto promised. Note that these efforts include fully mechanising cultivated land with at least 30% irrigated. Here is a breakdown of the funds’ application:

Table 4:

To deliver the economic benefits of the effort described above will require road and market components. These components include processing, transportation, storage, and effective local and export markets. They constitute the full compliment of an agricultural system and come at an additional cost of about US$126 billion. Notably, this kind of effort may more than double Nigeria’s current agricultural output, some of which will go to exports. These efforts will come with financial needs and execution complexities.

As tempting as it may be for Nigeria to hand its agriculture over to a Dangoteresque’s arrangement for effective delivery, it may not be the right direction. While it worked with petroleum product refining, the reality is that there is a need to decentralise delivery to several players (even if they act as a consortium). These efforts will be phased to grow land clearing, irrigation, mechanisation, processing, and logistics capacity. The value chain (crops and livestock) participation that improves food supply and export earnings also requires attention. A system that intentionally optimises Nigeria’s farm-to-table capacity and growing youth entrepreneurship and jobs is being built.

Agriculture financing approach with multi-sector players

To improve the chances of success and sustainability, this outlook will require a planned incremental delivery and overhauling of the agricultural system. Four critical components of this system are primary production, logistics and processing and markets. They need financing and must grow in tandem to make the best use of the additional capacity that Nigeria’s agriculture will experience.

Table 5:

Just as Dangote Refinery did for petroleum, a consortium of private sector players must collaborate with the custodian of the farthest-reaching and most effective mechanisms that support public sector efforts in agriculture financing, technical areas and market making. These custodians must be well-purposed to drive the delivery of the commitments to agricultural transformation and youth productivity through agriculture.

By mobilising public and private entities to fund, implement, and manage a private sector-led approach, we can address the challenges of Nigeria’s fragmented and underperforming agricultural system’s challenges. This entails providing land clearing, irrigation, mechanisation, processing, logistics, and market solutions. Such initiatives have the potential to yield significant results and empower a new generation of farmers in a relatively short time frame.

This model will employ Public sector resources to guarantee the invested funds of the Private sector and the People in a Partnership (PPPP). It will enhance the entire value chain, define categories and responsibilities for each player within it. Also, it will create ample opportunities for an impressive return on investment (ROI), support strong management and governance practices, and derive effectiveness and efficiency from private sector participation.

Table 6:

Financing this effort requires prioritising ventures to derive the most value from every money spent. The private sector consortium will ensure multi-dimensional value creation in capital appreciation, cash flow, profit, dividend, and taxes.

Fee proceeds and successful debt, and equity guarantees will contribute to Credit Risk Guarantee (CRG) pool growth. Then, available debt financing capacity will grow. Thus, long-term debt for capital expenditure and venture funds and short-term debt for operating expenses remain available.

A blended financing model may make it easier

A blended financing model is a solid approach to consider. It is where the syndication of three entities provides three distinct categories of financing. Each category focuses on long- or short-term finance requirements in debt and equity frameworks.

The proposed private sector consortium will lead an effort to finance the rapid transformation effort through financing land clearing, irrigation, farming, processing, logistics and markets. They may need to create a model that integrates the categories of financing defined in a blended financial model of debt and equity.

Furthermore, a CRG will support adequate debt and equity guarantees provided by private sector financial entities. Meanwhile, it will support the technical assistance elements required for proper fund deployment, utilisation, and governance.

Table 7:

With this model can repay capital expenditure (CAPEX) investment for land clearing, irrigation, mechanisation, logistics, processing and market infrastructure development in less than ten years. That is, at an interest rate of 10% per annum (low double-digit development finance credit) and if approximately 10% of annual revenue goes toward repayment.

Operating expense (OPEX) investments should cycle out profitably per periodic production cycle. However, operating expense funding will be available for two years, allowing users to turn the fund around between two and four times, depending on their trade and position in the value chain. This assumes there are no unforeseen occurrences and circumstances like natural disasters or negative price movements, which weather and yield index insurance will cover.

Table 8:

Scenario analysis: Absolute values of funding and share of total revenue to servicing interest and repayment of debt and dividend from investment

Assumptions:

– Best case scenario of 5 tons/hectare/cycle in 2 production cycles per annum for irrigated land

– 3 tons/hectare/cycle in 1 production cycle per annum for non-irrigated land

– Interest rate of 10% per annum with 10-year tenure for long term debt

– Interest rate of 20% per annum with 2-year tenure for short term debt

As this article has shown, financing an agricultural transformation requires a new kind of approach. Fortunately, it will not be altogether new to policymakers as Aliko Dangote has set an example with his refinery. The challenges uncovered and solutions proffered here are just one part of looking at agricultural financing in the country. The following article will explore how government agricultural intervention systems have led to missed opportunities and a new path.

I think Nigeria can. However, over the years, Dangote has successfully been able to build successful businesses across Africa to make the Government be able to invest in his refinery asides the urgent need for it as nation. With trusted farmers and profitable records and reliable Agric Tech company like AgroMall, the Nigerian government can finance it. It is a matter of time.

Lastly, I must commend your blended financing model recommendation, it definitely would make it easier.