Three questions answered in this article:

— Why is Nigeria struggling to achieve its agricultural export potential?

— What steps should Nigeria take to boost agricultural exports?

— How can Nigeria integrate agriculture into national economic planning?

President Bola Ahmed Tinubu stressed the need for substituting agricultural inputs and exporting agricultural products for foreign exchange receipts during the 2025 budget presentation to the National Assembly.

Like many of his predecessors, he continues a cycle of big ambitions and policy narratives. For years, we have heard similar plans, but we see no real improvements as administrations change.

A subsistence mindset in agricultural planning

Isn’t it ironic that while we aspire to export agricultural produce, our calculations for requirements focus solely on domestic consumption, reflecting a mindset of mere subsistence?

This is just like the subsistence (smallholder) farmers in rural Nigeria who only produce what they eat, which several narratives and efforts seek to change. It then begs the question of whether Nigeria is learning from the subsistence farmers or if it is the other way around.

What is certain is, to make progress in agricultural export, Nigeria must move away from requirement computation for subsistence, and do so for a combination of local consumption, commerce and export.

Nigeria’s agricultural data is often unclear due to a lack of transparent foundational assumptions. Different sources, such as the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Bank, and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), frequently report varying figures.

However, despite these differences, one notable trend remains: our agricultural requirements are typically based only on domestic consumption, even though we aim for commercial farming and exports.

The case of rice: a national-scale subsistence approach

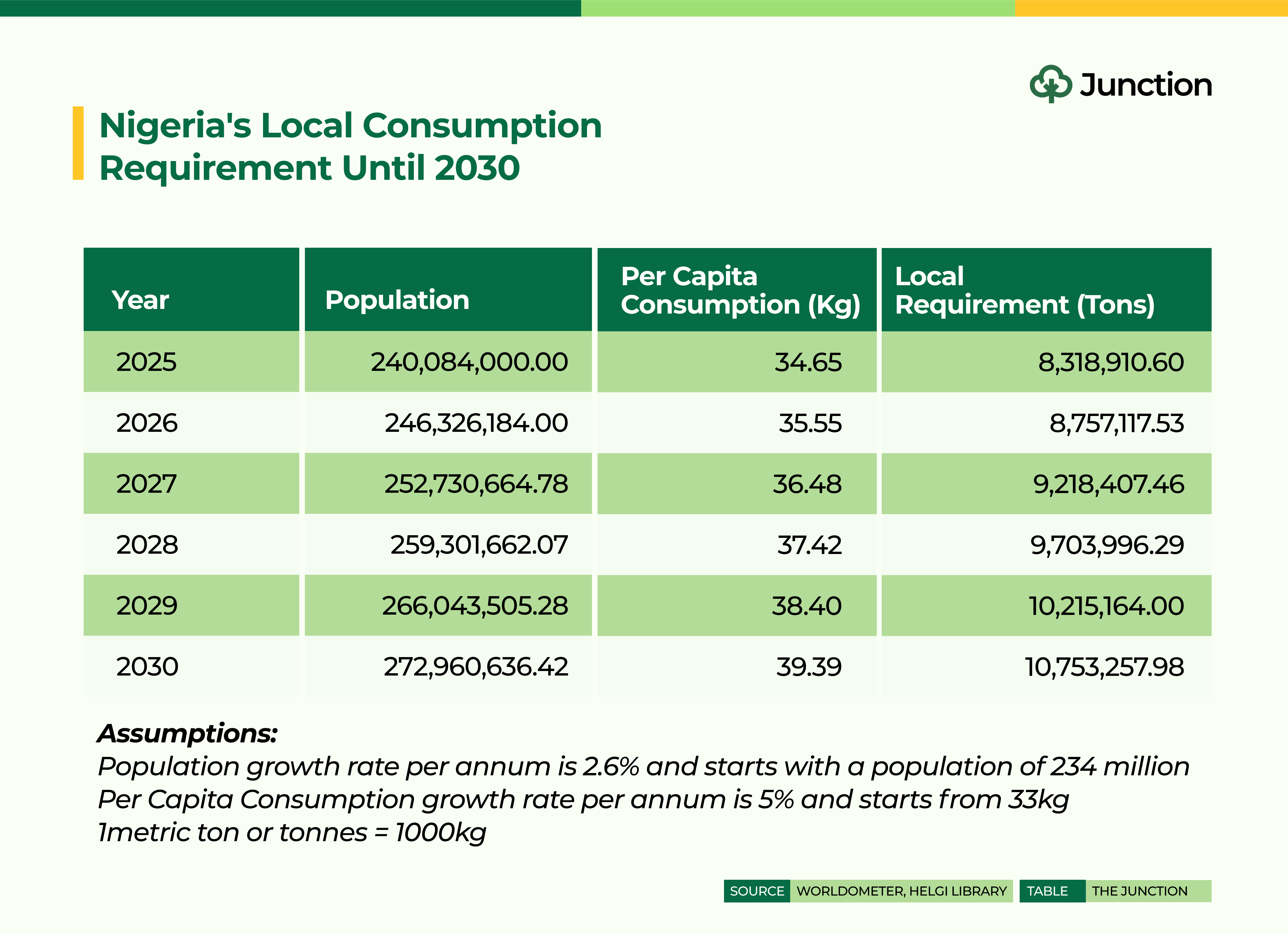

Take rice, one of Nigeria’s staple crops. Estimates suggest Nigeria requires about six million tons of rice annually. A straightforward calculation—using a per capita rice consumption of 33 kg and a population of 234 million—reveals that this estimate only accounts for local consumption and sustenance. In essence, subsistence agriculture is applied at a national level.

To accurately determine Nigeria’s agricultural needs, we must adopt a structured approach that aligns with national growth and export ambitions:

- Accurate Population and Consumption Data – Policymakers must establish reliable figures for Nigeria’s population and food consumption.

- Growth Rate Assessments – Future projections should align with realistic population and economic growth trends.

- Beyond Simple Calculations – Moving beyond basic methods like dividing total production by population or multiplying per capita consumption by population is crucial. These approaches fail to consider economic expansion and developmental aspirations.

- Export Market Outlook – The available export opportunities must be analysed and incorporated into agricultural requirement computations.

In simple terms, clear and measurable targets should be set for local consumption growth and export ambitions. These targets should include pricing, per capita consumption, export market share, and foreign exchange earnings.

Taking these methods into consideration, Nigeria’s local rice consumption requirement numbers should look like this:

Cross-border trade: an overlooked economic opportunity

At the beginning of the food crisis of 2024, caused by unavailability and pricing, reports indicated that Nigeria’s food, especially staples like maize and rice, were finding their way across the border to Niger Republic and other countries.

Rather than see this as an opportunity to understand consumption patterns of these countries and position Nigeria to supply, policymakers and government officials reacted by clamping down on this cross-border trade, thereby treating an economic opportunity like a crime.

Regardless, this is a strong indicator that there is a market for Nigeria’s agricultural and food exports, at least to its immediate West African neighbors. Thus, the requirement and our market participation outlook should be factored into the computation of agricultural and food requirements.

Setting clear agricultural export targets

Clear qualitative and quantitative targets must support such ambitions as supplying food to West Africa, especially as the right computation of requirements is a focus.

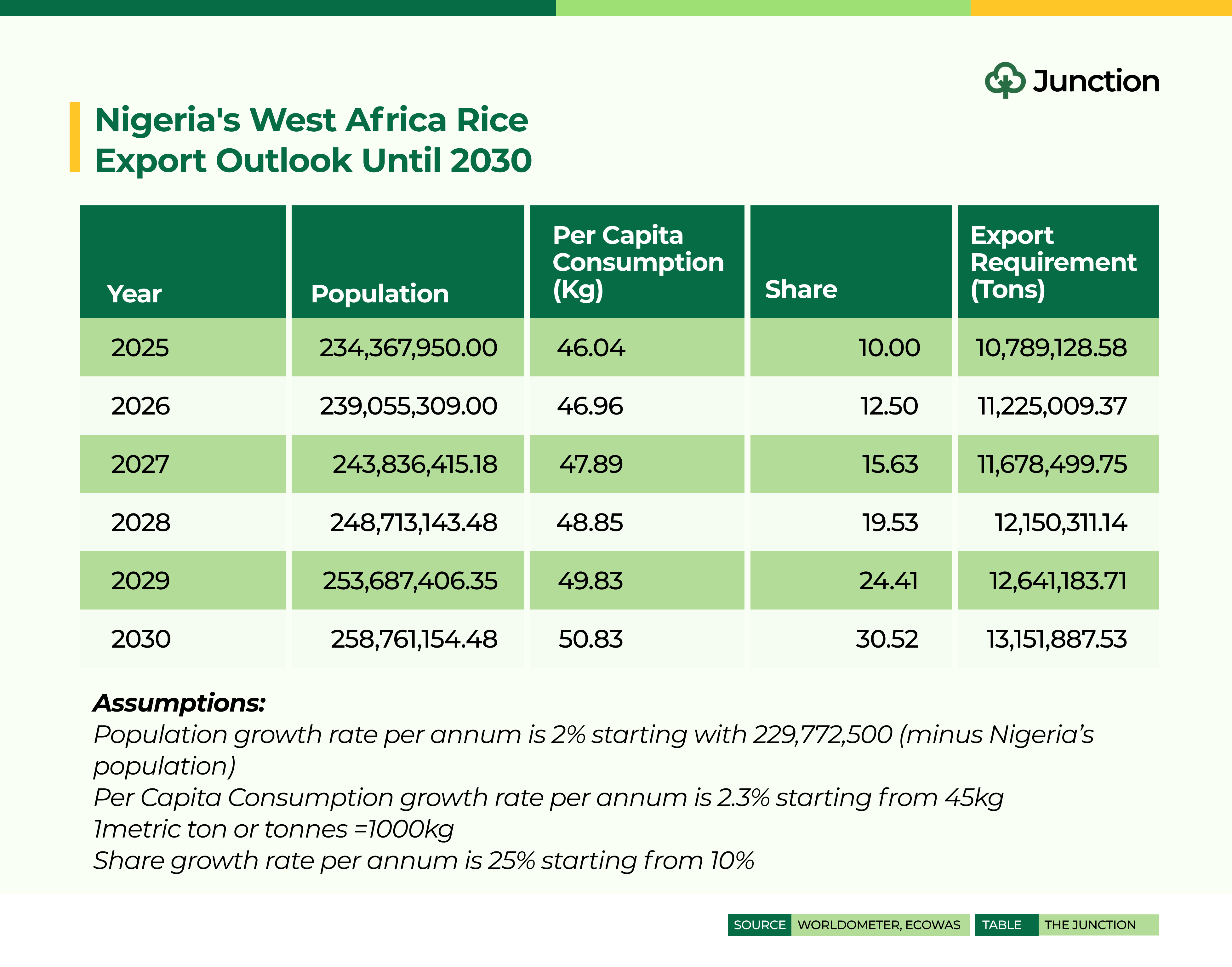

For example, such clarity as starting with substituting 20% of West Africa’s rice imports with Nigeria’s supply and growing the same by 10% per annum for 10 years must guide our outlook.

Our export outlook numbers for West Africa should look like this:

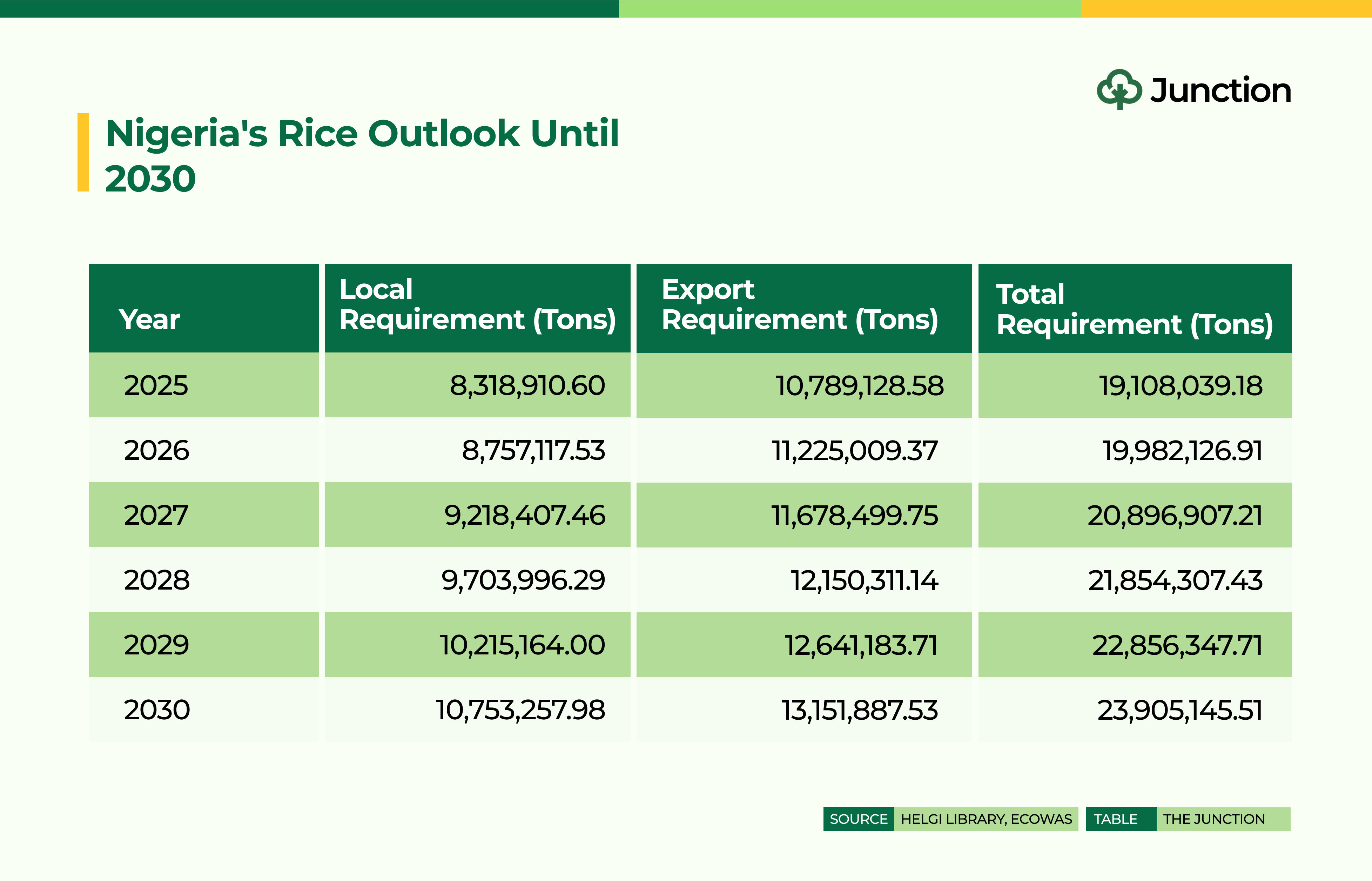

Applying a more comprehensive approach to rice production calculations suggests that Nigeria could be missing an export opportunity of about 23.9 million tons in the five years leading to 2030.

At current retail prices of $431 per ton, this amounts to approximately $10.3 billion—around $2 billion per year in lost potential revenue.

West Africa is a major rice importer, with imports covering about 40% of its consumption needs, and the region is responsible for 18% of the world’s rice imports.

However, to successfully export rice to West Africa, Nigeria must adopt a commercial and competitive approach:

- Cost Competitiveness – Nigerian rice must be cheaper than alternative imports. Geographical advantages should be leveraged to reduce costs.

- Production Efficiency – Improved agricultural practices and supply chain management can lower production costs.

- Regulatory Support – A streamlined process at customs and excise can facilitate smoother exports.

- Trade Agreements – Nigeria must take full advantage of regional trade liberalization provisions under ECOWAS and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

Beyond competitiveness, it is important that Nigeria sweats its economic treaty assets, and makes them work for its export outlooks, especially in agriculture. The sector can show almost immediate results, it is not complex, it has a short lead time, and there are existing support structures and production assets. Also, this sector offers participation to a large segment of the population.

Incorporating agriculture into national budgeting

To take agricultural and food exports seriously, their economic impact must be a key part of Nigeria’s national budgeting and trade planning. Where possible, this should also be broken down to the state level.

Nigeria aims to move beyond its dependence on oil, as the opening sentence of this article pointed out. At the same time, our agricultural sector produces a variety of crops, meaning we need a broader export strategy. To achieve this, we must create a framework that includes multiple agricultural products with strong existing and potential export demand.

One way to do this is by developing an agricultural export index for national budgeting and planning. This index should include, for example, five key crops that reflect pricing trends, production capacity, competitive advantages, and national aspirations. Each crop’s contribution should be weighted and valued in US dollars. Like petroleum, this index should serve as a benchmark for economic planning. The selected crops and their weights should be periodically reviewed and adjusted based on market realities and national goals.

Adopting an outward-looking trade strategy

Nigeria’s trade strategy must also adopt an outward-looking approach. While attracting investment is important and commendable, equal effort must be made to drive outbound trade. Given its potential and the relatively short time required to see results, agricultural exports should be a core pillar of Nigeria’s trade strategy, even influencing diplomatic relations.

Policymakers frequently emphasise the importance of agricultural exports, but it’s time to turn words into action. This means making agricultural exports a central focus in national planning and budgeting. The extent of its contribution should also be reflected in how we calculate our agricultural requirements.

Tying agricultural investments to measurable outcomes

Accurately calculating Nigeria’s agricultural requirements is not enough on its own. Without strategic investments in planning, funding, and execution, these numbers will not translate into real productivity or economic benefits. Clear objectives and strong links between strategy and outcomes are essential.

As Nigeria pushes for more investment in key sectors to boost foreign exchange earnings and national development, agriculture, particularly the value chains that support a proposed budgeting index, must receive the same level of attention as industries like petroleum.

Every naira invested in agriculture should be tied to measurable objectives. Key performance indicators, such as staple food security and export earnings, must be tracked, improved, and reported to Nigerians regularly.

Conclusion

Nigeria has the potential to become a major player in agricultural exports, but this requires a fundamental shift in how we compute agricultural requirements. Moving beyond subsistence-based calculations to a model that incorporates commercial farming and export ambitions will unlock significant economic opportunities. A well-structured approach—one that includes accurate data, growth projections, export targets, and competitive strategies—must guide national planning. By integrating agriculture into national budgeting and trade policies, Nigeria can create a framework that supports sustained agricultural growth while reducing dependency on oil revenues.

To achieve this, policymakers must commit to clear and measurable objectives that align with both domestic food security and export market expansion. Strategic investments in agriculture must be backed by performance metrics, ensuring transparency and accountability. By leveraging trade agreements, optimising production efficiency, and embracing a more outward-looking trade strategy, Nigeria can maximise its agricultural potential. Now is the time to move beyond rhetoric and take decisive action—agriculture must be at the heart of Nigeria’s economic diversification efforts.